1.21 Pernatal mortality

Page content

Why is it important?

The perinatal mortality rate includes fetal deaths (stillbirths) and deaths of live-born babies within the first 28 days after birth. Almost all of these deaths are due to factors that occur during pregnancy and childbirth. Perinatal mortality reflects the health status and health care of the general population, access to and quality of preconception, reproductive, antenatal and obstetric services for women, and health care in the neonatal period. Broader social factors such as maternal education, nutrition, smoking, alcohol use in pregnancy, and socio-economic disadvantage are also significant.

Findings

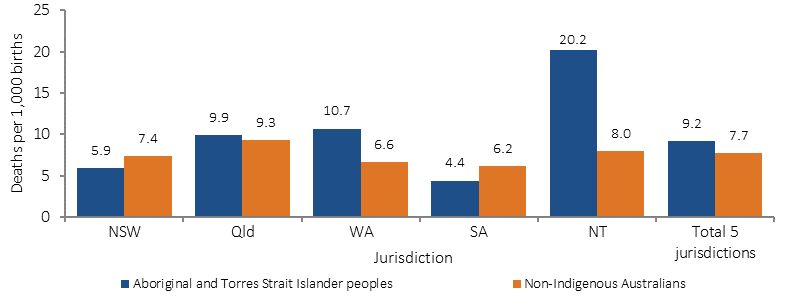

Reliable data on fetal and neonatal deaths for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are only available for NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT. Based on the combined data for these jurisdictions for the period 2011–15, the perinatal mortality rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies was around 9.2 per 1,000 births compared with 7.7 per 1,000 births for non-Indigenous babies. Fetal deaths (stillbirths) account for around 59% of perinatal deaths for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies and 70% of perinatal deaths for non-Indigenous Australian babies.

Due to small numbers, time-series data for perinatal mortality are volatile. The perinatal mortality rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples decreased by around 56% between 1998 and 2015—an average yearly decline of 0.6 deaths per 1,000 births. The perinatal mortality rate for non-Indigenous Australians also decreased, but by a smaller amount, so that the gap between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians decreased significantly over this period. Fetal death rates for Indigenous Australians declined by 53% and neonatal deaths by 60%.

Estimated rates for perinatal mortality vary between jurisdictions from 4.4 deaths per 1,000 births to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers in SA, to 20 per 1,000 births in the NT. The largest gap was in the NT with Indigenous rates 2.5 times the non-Indigenous rates. Indigenous perinatal mortality rates were lower than non-Indigenous rates in NSW and SA.

The leading cause of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perinatal mortality was a group of conditions originating in the perinatal period including birth trauma and disorders specific to the foetus/newborn (accounting for 44% of deaths), followed by premature birth/ inadequate fetal growth (30%). Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities were the third most common group of conditions (15%). The main conditions in the mother leading to perinatal deaths were complications of the placenta, cord and membranes, followed by complications of pregnancy (both 13%). When looking at the pattern of causes of death in the first 28 days, a higher proportion of Indigenous deaths were due to premature birth/inadequate fetal growth (30% compared with 21% non-Indigenous) and a lower proportion due to congenital malformations (15% Indigenous compared with 21% non-Indigenous).

Maternal health factors such as pre-pregnancy weight and diabetes have been linked to birth outcomes and infant mortality. A significant association between maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth has been found (Yao et al, 2014).

Figures

Figure 1.21-1

Perinatal mortality rate by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA, and the NT, 1998 to 2015

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

Figure 1.21-2

Perinatal mortality rate by state/territory and Indigenous status, 2011–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database Table 1.21-1

Table 1.21-1

Proportion of deaths for perinatal babies by underlying cause of death and Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2011–15

| Cause of death | Foetal deaths | Neonatal deaths | Perinatal deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | Indigenous | Non-Indigenous | |

| Per cent | ||||||

| Main condition in the foetus/infant: | ||||||

| Other conditions originating in the perinatal period | 61.6 | 59.2 | 19.0 | 25.0 | 44.0 | 48.8 |

| Disorders related to length of gestation and foetal growth | 21.8 | 17.0 | 43.0 | 31.0 | 30.4 | 21.1 |

| Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 13.9 | 18.8 | 17.0 | 25.0 | 14.9 | 20.7 |

| Respiratory and cardiovascular disorders | 2.3 | 3.5 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 5.6 |

| Infections | np | 0.9 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| Other conditions | — | 0.6 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| Main condition in the mother: | ||||||

| Complications of placenta, cord and membranes | 14.8 | 15.1 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 14.2 |

| Maternal complications of pregnancy | 8.9 | 8.4 | 18.4 | 14.9 | 12.8 | 10.4 |

| Maternal conditions that may be unrelated to present pregnancy | 6.8 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 4.7 |

| Complications of labour and delivery and noxious influences transmitted via placenta or breast milk | 5.9 | 4.0 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 4.8 |

| Total deaths (Number) | 440 | 5,524 | 310 | 2,407 | 750 | 7,931 |

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

Figure 1.21-3

Child and infant mortality, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2011–15

Source: ABS and AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database

Implications

Rates of low birthweight for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies have declined by 13% from 2000 to 2014 (see measure 1.01).

A study of avoidable mortality in the NT between 1985 and 2004 found a significant improvement in mortality for conditions amenable to medical care for Indigenous Australians in the NT, including perinatal survival. The authors noted that a broad range of medical care improvements such as an increased number of births in hospital, improved neonatal and paediatric care, and the establishment of pre-natal screening for congenital abnormalities have likely contributed to this improvement (Li, SQ et al, 2009). Due to small numbers it is not possible to detect statistically significant changes in particular causes of perinatal deaths.

Enhanced primary care services and continued improvement in antenatal care have the capacity to support improvements in the health of the mother and baby.

Recognising this, the 2014–15 Federal Budget provides funding of $94 million from July 2015, for the Better Start to Life approach to expand efforts in child and maternal health.

The Better Start to Life approach includes $54 million to increase the number of sites providing New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services from 85 to 136. These Services provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families with access to antenatal care; practical advice and assistance with parenting; and health checks for children.

This approach also provides $40 million to expand the Australian Nurse- Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) from 3 to 13 sites. The ANFPP aims to improve pregnancy outcomes by helping women engage in good preventive health practices; supporting parents to improve their child's health and development; and helping parents develop a vision for their own future, including continuing education and finding work. A study of the impact of the US Nurse Family Partnership program, on which the ANFPP is modelled, has shown reductions in all-cause mortality among mothers and preventable-cause mortality in children in disadvantaged settings (Olds et al, 2014).

The Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) is in the process of developing Guiding Principles for Birthing on Country Service Model and Evaluation Framework to build upon the National Maternity Plan.

The Department of Health coordinated the development of National Evidence-Based Antenatal Care Guidelines on behalf of all Australian governments. The Guidelines were developed with input from the Working Group for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Antenatal Care to provide culturally appropriate guidance and information for the health needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pregnant women and their families.

The Antenatal Care Guidelines are intended for all health professionals who contribute to antenatal care including midwives, obstetricians, general practitioners, practice nurses, maternal and child health nurses, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers and allied health professionals. They provide consistency of antenatal care in Australia and ensure maternity services provide high-quality, evidence-based maternity care.

In 2016, the Department of Health began a review and update of the Antenatal Care Guidelines. One of the topics to be reviewed is the Antenatal Care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women. This topic will consider how holistic antenatal care can be provided to meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women including spiritual, emotional, social and cultural as well as physical and health care needs. A draft version of the revised Antenatal Care Guidelines is expected to be released for public consultation early in 2017 with final guidelines expected to be completed in mid-2017.

The Australian Government also funds the development of nationally consistent maternal and perinatal data collections. Improving data collections is critical to informing actions to improve outcomes for mothers and babies, including reducing perinatal mortality.